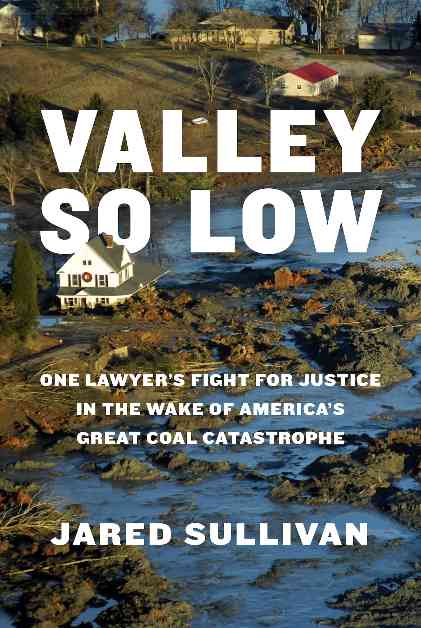

The Tennessee town of Kingston was thrust into the spotlight just before Christmas in 2008 when a devastating coal ash flood swept through the area surrounding the Kingston Fossil Plant. A towering pile of coal ash, a residue from burning coal that had accumulated over five decades in what was once a serene swimming hole, broke free and unleashed a wave of destruction across 300 acres of land, eventually spilling into the Emory River Channel. Described as a “black wave” resembling a tsunami, the flood left a trail of devastation in its wake, destroying dozens of homes and displacing families in its path.

Jared Sullivan, the author of Valley So Low, vividly recounts the harrowing aftermath of the disaster in his new book. He paints a vivid picture of the coal ash spill, likening it to a force of nature that engulfed the town in darkness. Sullivan’s firsthand account of the events sheds light on the environmental catastrophe that unfolded in Kingston and the ensuing legal battle for justice against the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) led by attorney Jim Scott.

As a child who witnessed the disaster unfold on the news, Sullivan recalls the initial assurances from authorities that the coal ash posed no significant risk to the community. However, as cleanup efforts began, it became apparent that the hazardous nature of the coal ash had been grossly underestimated. Workers tasked with cleaning up the site were not provided with adequate protective gear, such as masks or hazmat suits, exposing them to toxic substances without proper safeguards.

Through his research, Sullivan uncovered alarming revelations about the toxic nature of the coal ash, which contained arsenic, lead, and radioactive materials. Despite internal documents dating back to 1964 that indicated the hazardous properties of the coal ash, the TVA continued to downplay the risks to public health. Tom Bock, a safety officer with Jacobs Engineering overseeing the cleanup, infamously claimed that the fly ash was “safe enough to eat,” a statement that starkly contrasted with the alarming health effects experienced by workers on the site.

The toll of the disaster on the cleanup workers was profound, with many falling ill and experiencing severe respiratory issues as a result of exposure to the toxic coal ash. Sullivan’s recounting of the workers’ suffering and the legal battle that ensued against Jacobs Engineering sheds light on the human cost of environmental negligence. Despite the eventual settlement offer in 2023, which the workers accepted, the impact of the disaster on their lives was irreversible.

Looking beyond the immediate aftermath of the Kingston coal ash spill, Sullivan reflects on the broader implications of the disaster for environmental policy and regulation. He highlights the shortcomings of the EPA in ensuring the safety of workers on site and emphasizes the need for stricter regulations to prevent similar disasters in the future. With hundreds of unlined coal ash dumping sites still posing a threat to groundwater and rivers across the country, Sullivan calls for greater accountability and oversight to protect public health and the environment.

In his passionate plea for reform, Sullivan underscores the importance of transitioning away from coal-fired plants towards cleaner energy sources like nuclear power and renewables. He sees an opportunity for the TVA to reclaim its legacy as a champion of public welfare by embracing sustainable energy solutions that prioritize environmental stewardship. By advocating for stricter regulations and corporate accountability, Sullivan hopes to prevent future environmental disasters and safeguard communities from the devastating impacts of industrial negligence.