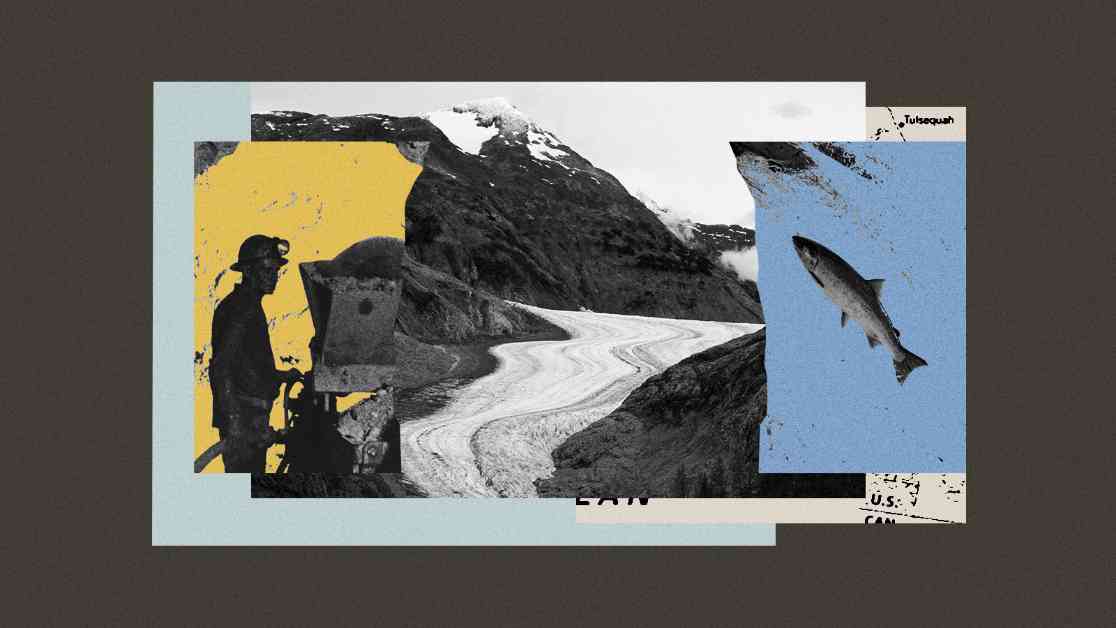

The Tulsequah Glacier, chilling in northwest British Columbia just 7 miles shy of the Alaska border, is doing a melting dance, creating a new lake at its feet. This lake, unnamed and mysterious, is still a bit too chilly and murky for salmon to call it home. But Jon Moore, an aquatic ecologist, believes that the future is bright for fish in this area. As the glacier retreats, the lake warms up and clears out, making it a prime spot for migrating salmon to take a dip. The potential for new salmon habitats emerging as glaciers melt is on the rise in Alaska and western Canada, offering a glimmer of hope amidst the climate change threats that salmon face.

The disappearing glaciers are not only opening up new opportunities for fish but also for the mining industry. With gold prices skyrocketing and the demand for copper on the rise, mining companies are flocking to areas previously covered in ice, hoping to strike it rich. While this mineral rush promises jobs and revenue for some communities, it’s causing concern among environmental advocates, Indigenous leaders, and fishermen downstream. The pollution from past mining operations, like the acid runoff from the Tulsequah Chief mine, serves as a cautionary tale of the potential dangers of mining in glacier-fed watersheds.

As the mining boom continues, conflicts arise between those who see the economic benefits and those who fear the environmental consequences. While some believe that mining can be done safely without harming salmon habitats, others are skeptical. The push and pull between economic development and environmental protection are at the heart of the debate surrounding mining in these regions. The future of both the mining industry and the salmon populations hangs in the balance as glaciers continue to melt, revealing new opportunities and challenges for all involved.